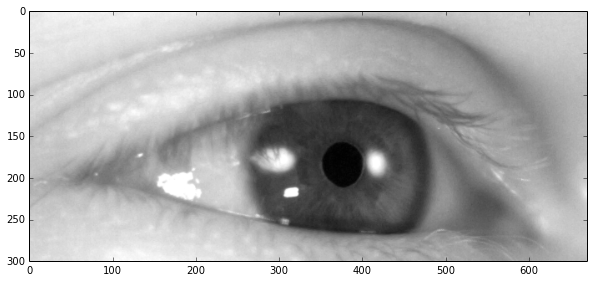

Pupil Detection will be the basis of my eye tracker. In the end it will rely on accurate and robust pupil detection, but for now a simple detector will do. Later I will revisit the detection when the basics of the other components are done.

The idea presented here is a simple one. If we look at the image, the pupil is just a black circle. Now this might not always be true, as in the circle does not always have to be completely black (in case we have some glints) and might not be a circle (if we're looking at the pupil under an angle). We will deal with these potential issues later, for now we'll just stick to the basics.

I will be using OpenCV 2 and Python 2.7.5 on OSX.

So on a high level, the process is the following:

- Load the image and convert it to grayscale

- Threshold the image

- Cleanup using closing

- Find the most circular contour

- Draw it into the original image

So here I just load the original image.

import cv2

import numpy as np

image = cv2.imread('eye.png')

gray = cv2.cvtColor(image, cv2.cv.CV_BGR2GRAY)

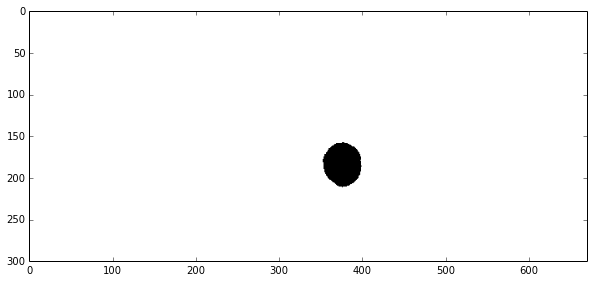

Now that that's out of the way, I'll threshold it. This will make a binary image out of a grayscale one. So everything darker than 30 goes to black, and everything else goes to white. And this is what I get.

retval, thresholded = cv2.threshold(gray, 30, 255, cv2.cv.CV_THRESH_BINARY)

Now this next part (Line 1 and 2) does not have to be here for this particular image, but in general it should be there, becuase you want to get rid of small holes that might occur in the pupil from glints, but since there are none in this image, it is of no concern.

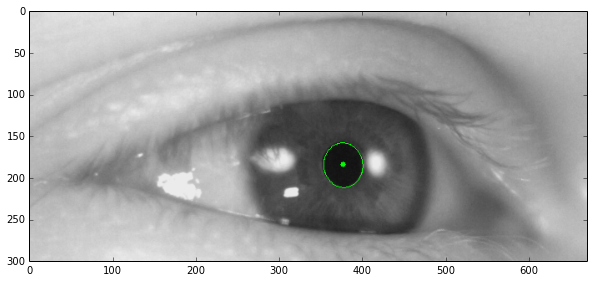

Now the binary image is fed into the

findContours

function, which will identify individual "objects"

in the image. In this case we get two, one is for the pupil and one is for the whole image. So how to

distinguish between the two? I used the extend parameter which puts in relation the area of a shape

to the area of its bounding box. This will be close to 1 for the whole image, because it is rectangular,

but lower for the pupil, since it is more circular. Something like

Convex Hull and

Arc Length

could be used to make this more robust. For example use the ratio of the radius to area. I will

revisit this topic in the future.

At last we compute the center of the detected area and fit an ellipse around it, so that we can draw the results into the last image.

kernel = cv2.getStructuringElement(cv2.MORPH_RECT, (10, 10))

closed = cv2.erode(cv2.dilate(thresholded, kernel, iterations=1), kernel, iterations=1)

contours, hierarchy = cv2.findContours(closed, cv2.cv.CV_RETR_LIST, cv2.cv.CV_CHAIN_APPROX_NONE)

drawing = np.copy(image)

for contour in contours:

area = cv2.contourArea(contour)

bounding_box = cv2.boundingRect(contour)

extend = area / (bounding_box[2] * bounding_box[3])

# reject the contours with big extend

if extend > 0.8:

continue

# calculate countour center and draw a dot there

m = cv2.moments(contour)

if m['m00'] != 0:

center = (int(m['m10'] / m['m00']), int(m['m01'] / m['m00']))

cv2.circle(drawing, center, 3, (0, 255, 0), -1)

# fit an ellipse around the contour and draw it into the image

ellipse = cv2.fitEllipse(contour)

cv2.ellipse(drawing, box=ellipse, color=(0, 255, 0))

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 5))

plt.imshow(drawing)

So that is how we quickly detect the position of a pupil in an image. In the next installments we will look at how to detect the iris, which is a bit more complicated. We will also flatten the iris out and then we will look at processing video.

This post is also available as a iPython Notebook